Wide Shot

The wide shot is primarily used to

establish the setting or location of a scene. Since objects appear small in

the frame, it can also be used for de-emphasis and is ideal for

conveying character isolation. This shot from Vertigo

accomplishes both of these goals:

The wide shot has two drawbacks: it

weakens the director's control over audience attention and lessens the

impact of action. It should be avoided when important detail must be

conveyed. Wide shots are also referred to as establishing shots.

Close Shot

The close shot is the exact

opposite of the wide shot in that the subject is very large in the frame.

Consequently, it is used for emphasis. When the subject is an actor,

anything closer than mid-chest is considered a close shot, or close-up.

Here, the actor's head dominates the composition. There are several types of

actor close shots, as illustrated in this still from The

Godfather:

Another variation is the over the

shoulder shot, where an actor is seen in close-up over another actor's

shoulder. This shot is often used in dialogue scenes as a bridge between a

shot of two actors and a close-up:

The close shot is a powerful tool and

should be used sparingly. When used too often, the audience becomes

desensitized to it and its effectiveness is lost.

Medium Shot

As the name indicates, the medium shot

falls between the close shot and the wide shot. When the subject is an

actor, the upper body dominates the frame, usually from the thighs up.

Movies are primarily constructed of medium shots, with wide shots and close

shots used for orientation and emphasis, respectively.

Multiple Sizes

A composition can have multiple subject

sizes. For example, one actor can be shown in close-up, while another is in

full shot. This enables the audience to follow action in the foreground and

the background simultaneously. The technique, called deep focus,

was pioneered by Orson

Welles in his landmark film Citizen

Kane. The following shot shows actors in close, medium, and full

shot:

Variable Size

The size of a subject can be varied

during a shot by moving the camera and/or subject. For example, an actor in

medium shot can move away from the camera into wide shot or toward the

camera into close-up. This shot from Shadow

of a Doubt moves from a medium shot to an extreme close shot:

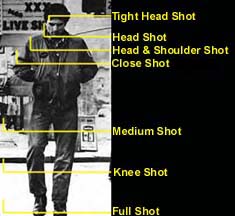

Cutting Heights

There must be a clear understanding

between director and cinematographer as to where frame lines cut off the

actor's body. These designations are called cutting heights:

A rule in cutting heights is that frame

lines should not cut through an actor's primary joints, since this has a

strange look on screen. Primary joints include the neck, waist, knees, and

ankles. The director should be aware that terminology may vary slightly from

one cinematographer to the next, so definitions should be clearly

established before shooting begins.

Technical

Considerations

The preferred way to change subject size

is to move the camera in relation to the subject, or vice versa. Subject

size can also be varied by changing the lens focal length (i.e.,

magnification), however, this affects the way the image looks in terms of

depth perspective and depth of field:

Depth Perspective - Depth

perspective is the apparent distance of the foreground and background in

relation to each other. Wide focal lengths expand the apparent distance,

while long focal lengths compress it.

Variation in Depth Perspective

(note size of people in background)

Depth of Field -

Depth of field is the amount of

acceptable focus behind and in front of the subject. Short focal lenses

tend to produce a wide depth of field, where everything on the set appears

in focus ("deep focus"). Long focal lenses produce a shallow depth of

field, where only the subject area is in focus.

Shallow Depth of Field

To avoid fluctuations in these variables

from one shot to the next, the cinematographer chooses a focal length and

shoots the entire scene with that lens. The camera is then moved in relation

to the subject to create the desired subject size.